By Kris Korzeniowski

From http://tcw2.ppsw.rug.nl/~gyas/wedstrijd/artikelen/techniek.shtml

Translated from Dutch by Jamie Croly

-----------------

Athlete’s technical capacity, condition and motivation determine the level of their performance. Although technique plays a role at all sports, rowing demands a considerable technical quality before a high performance level can be reached. It makes no sense to train for strength, endurance and other physiological aspects if a rower does not have the skills to use these for increasing the boat speed.

Frequently smaller and weaker athletes can compete with stronger and bigger athletes because they are technically better.

Coaches must concentrate on the basic principles of the rowing technique. By continuing to focus on the basic principles you can both begin and progress athletes development. A lot of experience and successful coaches have simplified their coaching of technique over the course of years.

As coach you must understand the basic principles of the rowing technique entirely and master this. You must have a clear picture of the rowing stroke and be to describe this in simple, terms clear to your rowers.

Natural rowing

The technique which is presented here is a logical, natural movement. There is no place for abrupt movements which disrupt the speed of the boat. Body movement, hendelvoering and drive must be in agreement with the speed of the boat.

At the beginning of the stroke the rower must place the spoon in the water, at the same time as the legs push against the stretcher. The upper body and the arms only give support: you hang on the oar whereas the legs are kicked off. At the end of the leg drive the upper body sways to the back, followed by fast bend of the arms. The legs, upper body and arms cooperate in a logical and natural order, each partially overlapping. Because of this a constant pressure is provided on the spoon.

If the rowers can maintain the idea of hanging, it will be not necessary them tell when to ' open the back ' or the arms to bend. Hanging on the oar dictates the natural movement order.

Another main point is that all movements are dependent on each other and in harmony is with the speed of the boat. This way the complete stroke cycle - irrespective of the tempo - seem simple, fluently and easy. Movements that are not fluid makes for wrong movements - abrupt accelerations, jerky movements – and are more clearly visible.

Phases of the Rowing Stroke

Rowing is a cyclic sport; rowers repeat the same order of movements each time. If we talk about the rowing stroke we also talk about the stroke cycle.

The stroke cycle consists of 2 phases:

The propulsive phase - drive - the spoon sits in water, and;

Recovery phase - recover - the spoon is above water and the rower slides forward (actually sternwards).

To develop a good picture of the rowing stroke, we these have subdivided positions:

Ø First half (beginning) of the recovery,

Ø Second half (in the middle of) of the recovery,

Ø Placement (catch) of the spoon in the water,

Ø First half (beginning) of the drive,

Ø Second half (in the middle of) of the drive, and

Ø The finish and extraction

Changes of the angles of knees, hips and elbows determine the work positions of the most important muscles in legs, back and arms. To simplify the learning process three control points the for each position are used:

Ø Knee angle - leg stipulates action and the place of the bankje

Ø Hip angle - the stipulate position of the upper body

Ø Elbow angle - arm position and arm ' work '

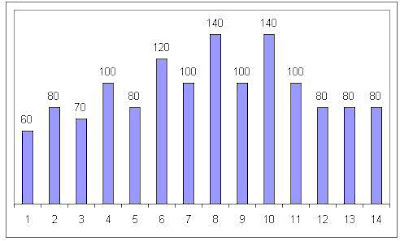

Fig 1. The angles of the most important muscle groups which are used in rowing.Left the angles at the catch, Right the angles at the finish.

The analysis of the stroke cycle starts with the first part of the recovery. During the recovery the rower not only slides forward, but the preparation (body preparation) for the critical moment of the placement of the spoon in water takes place.

Insufficiently forward body angle causes a range of errors: with hands and shoulders diving into the boat at the catch, the spoon moves, invegen from water, etc. For this reason the importance of good recovery and body preparation cannot be emphasized sufficiently.

Sculling

First half of the recovery

The knee angle is flat, the seat is in the hindmost position.

The hip angle is open; the upper body is in ' lay-back ' position.

The elbow angle is flat; the arm has been stretched and the upper body moves from Lay-back to a more upright position. Then the glide phase starts forward.

This position is a very important point in first half of the recovery. The body is still in lay-back the position, whereas the hands move away from the body.

Second half of the recovery

The knee angle has been bent slightly; the seat is itself in the middle of the slide.

The hip angle is rather sharp; the body leans forward to maximum reach.

The arms have been stretched. It important that the arms are fully stretched has been stretched body position fixed, so that you only slide to the catch.

Placement of the spoon in the water - the Catch

The knee angle is sharp; shins are in full compression almost vertical position

The natural body attitude has been bent forward slightly from the hip reaching with the upper body. The sitting position is ' high ' and relaxed; you use complete length and reach.

The arms have been stretched entirely.

First half of the drive

The knee angle becomes flatter. After the placeemnt of the spoons in the water, the body weight is transmitted on the stretcher by use of leg strength. The seat has been pushed back.

The hip angle remains the same. Because of this horizontal power application occurs. The muscles in back, shoulders and arms give backpressure, as a result of which a good link between legs and spoon occurs. The upper body does not come over.

The arms remains stretched.

Second half of the drive

The knee angle is almost completely flat. The seat sits on the last quarter of the sliding. The legs are themselves in very efficient position, flat for the last push down.

The hip angle has been opened; the body swing supports the leg drive. The upper body is high and (almost) vertical.

The arms are still stretched, ready for them to start bending. At crossing the hands the bowside hand is flat above the stroke side hand.

The oars come almost perpendicular on the boat, mechanically a very efficient part of the stroke. The body weight hangs still between the oars and the stretcher.

The Finish and Extraction

The knee angle is flat and the seat is in rearmost position. The legs and back are almost completed. The legs continue to push against the stretcher, through the finish.

The hip angle is open, the torso is in the lay-back position, approximately 25 degrees past the vertical. The head and the shoulders are behind the handles.

The elbow angle decreases as the hands move to the finish, supported by firm push of the legs against the stretcher. The forearms are horizontal.

You must maintain pressure on the spoons, in spite of acceleration the boat.

At extraction the hands finish a circle movement down and away, without touching the body. The bow side is flat above the stroke side hand, until the hands are next to each other and at the sides of the body.

Sweep Rowing

First Half of the Recovery

The knee angle is flat, the seat is in the hindmost position.

The hip angle is open; the torso is in lay-back position.

The elbow angle is flat; the arms has been stretched and ' draws ' the torso from lay-back to a slightly forward leaning position. Then the glide phase begins.

This position is a very important point in first half of the recovery. The body is still in lay-back the position, whereas the hands move away from the body.

Second Half of the Recovery

The knee angle has been bent slightly; the seat is in the middle of the slides.

The hip angle is rather sharp; the body is ready with forward lean (body preparation). The outside shoulder is further stretched and is higher than the inner shoulder.

The arms have been fully stretched. It important that the arms have been completely stretched and the body pivoted forward, so that you must slide only to the catch.

Placing of the spoon in the water – The Catch

The knee angle is sharp; shins are in full compression almost vertical position.

The natural body attitude has been bent forward slightly from the hip reaching the torso. The armpits are high and relax themselves, you use yourself complete length and reach. The outside shoulder keeps a little higher than the inner shoulder.The arms have been stretched entirely.

At maximum reach the spoon goes into the water. The back does not rise; only the hands place the spoon in water. The speed of placement is critical. You want you ensure that the optimal place for the catch is not missed. The efficiency of the leg drive will be lost if the spoon is not put immediately complete in water.

First Half of the Drive

The knee angle becomes flatter. After the placement of the spoons in water, the body weight is transmitted on the footboard by use of leg strength. The seat has been begun to move.

The hip angle remains the same. Because of this horizontal power application occurs. The muscles in back, shoulders and arms give back pressure, as a result of which a good link between legs and spoon arises. The torso does not rise.

The arms remains stretched. The outside shoulder has most of the tension.

Second Half of the Drive

The knee angle is almost completely flat. The seat sits on the last quarter of the sliding. The legs are themselves in very efficient position, flat for the last push down.

The hip angle has been opened, the body swing supports the leg drive. The torso is high and (almost) vertical.

The arms are still stretched, and about to start bending.

The oars come almost perpendicular on the boat, and are in a very mechanically efficient position. The body weight hangs still between the oars and the footboard

The Finish and Extraction

The knee angle is flat and the seat is in hindmost position. The legs and back are almost finished. The legs continue push finishing against the footboard, well supportive.

The torso comes in maximum lay-back; the outside shoulder is a little higher than the inner shoulder. The head and the udder are themselves behind the oar.

The elbow angle decreases as the hands approach the finish, outside forarm is horizontal

At the extraction the rower in lay-back position. The hands finish a circle movement down and away, without touching the body.

Grip

Beginners must learn a correct grip of the oar early. A wrong grip causes a lot of errors and is not easily correct. Did not be afraid to invest time in teaching a correct grip for beginners. Teach them how to hold an oar before anything else, Every training session should start with attendtion to the correct grip and rotation of the oar.

Sculling Grip

The scull grip must be relaxed to be with one's index fingers on the end of the handle and the thumb on the end of the handle.

The other fingers have been bent around the grip. The palm is not on the handle and the wrist remains virtually flat, both during the drive and the recover.

Twisting at release and catch happens by use of the fingers, as a result of which the handle ywsts in the fingers. The wrist remains flat.

Sweep Grip

The hands are approximately 2 hand breadths from each other have been put on the oar handle.

The fingers joints have been bent for the grip, with thumbs under the handle.

Both wrists are flat, with the hand palms apart from the handle. The oar must be carried by the fingers, not to be held in the hands.

At extraction the fingers of the outside hand press the handle down. (At sweep rowing the outside arm is most distant from the spoon). The oar is twisted by movement of the inner hand. It is important that the outside wrist remains flat. The outside wrist of the rowers remains flat, whereas the oar in the fingers rotates.

Squaring happens by the fingers and thumb of the inner hand, where the fingers of the outside hand remain around the handle. Twisting the handle, both at catch and extraction, in done by only the inner hand.

The outside hand remains relaxed and flat, as a result of which the rower can rotate the handle in the fingers. The use of the outside hand and arm in the catch is very important, because the outside arm has a longer gearing. The fingers of the outside hand cannot be ' separately ' of the oar. The outside hand and arm must be prepared immediately after the catch to take the pressure.

Blade Work

The blade work has direct consequence on the movement and speed of the boat. For this reason many coaches give more attention on correct blade work than to the body movement. However, the blade work is an direct consequence of what happens in the boat. It is possible for the body movement or the blade work to change and on the other hand improvements to see. An example of good blade work

During the recovery the spoon moves in a smooth, horizontal movement toward the bows. The rower must have sufficient space to square the spoon, without touching water.

Squaring for the Catch

Ideally twisting the spoon starts as the hands move over the ankles. Turns must happen quietly, during the last bit of the recovery. It must not influence the horizontal movement of the spoon.

The Catch

The placing of the spoon in water happens rapidly, as a continuation of the recovery. It must be coordinated on the speed of the boat, without much back-splash or front-splash. For beginners however, a small back-splash is advised, to ensure that no water is missed. The weight of the oar does not ensure the catch speed. The placing of the spoon in water, must be followed immediately by the horizontal power application as the blade is covered.

Drive

During the drive the spoon must sit 2-3cm under the water. Because the boat accelerates during the drive, it is important also the handle accelerate, as a result of which the horizontal movement is maintained.

Extraction

The rower must make a smooth, fluent, half-round movement, to get the spoon out of the water. Feathering happens after the spoon is out of the water.

The path of the spoon must be linked both during the drive and the recovery by horizontal movements, and by round movement, as the oars change direction.

The complete movement (turns, catch, extraction and recovery) must related be to the speed of the boat and the tempo.

Summary

The basic rowing technique is a logical, natural movement. There is no space for drastic, abrupt movements which limit the speed of the boat. Body action, blade movements and movements of the seat must be all in harmony with the speed of the boat.